4 minutes

The two need to be aligned, and the culture that aligns best is a learning one.

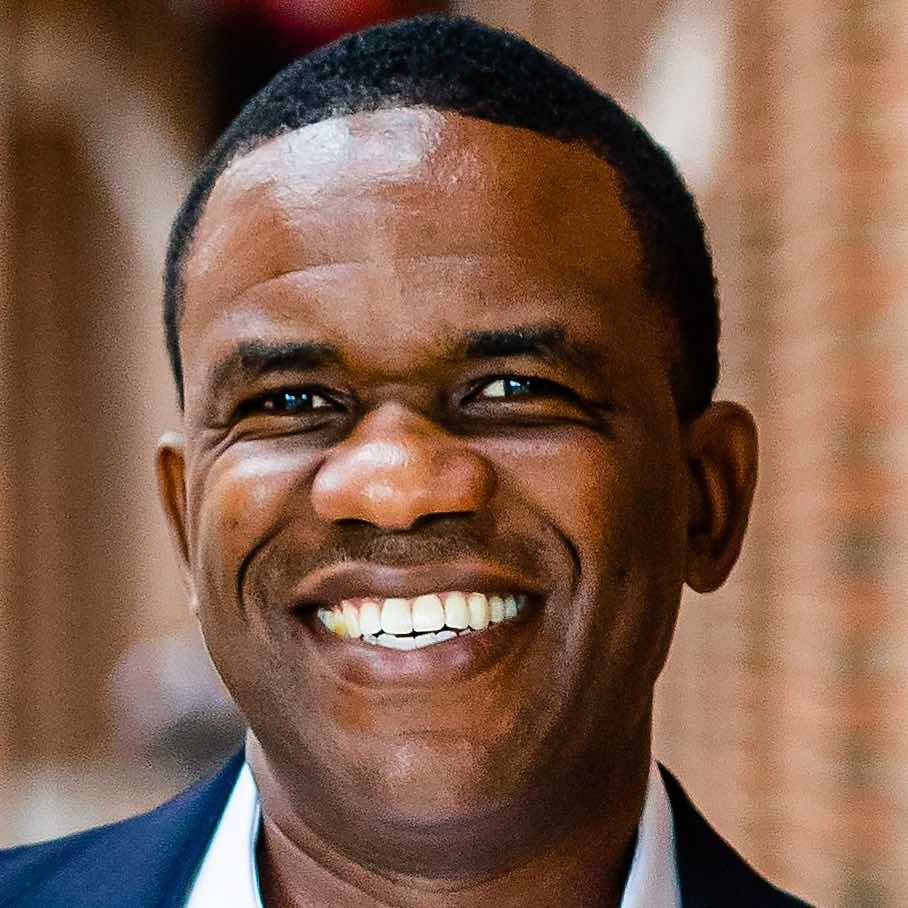

A “strong” culture is good in times of stability, according to Sekou Bermiss, Ph.D., associate professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who presented two sessions for CUES’ High Performing Boards Digital Series. “When you know exactly what you’re going to be dealing with, then a strong culture, and everyone’s on the same page, is really good.

“But a good culture is not always a strong culture,” Bermiss added. “If things are changing, a strong culture can actually be a detriment. It can ... create blind spots.”

Bermiss explained that culture is about “the norms, about what is considered legitimate and illegitimate within a company.” Culture answers such questions as what are the ways we do things here and what are we about.

“I don’t think culture eats strategy for breakfast,” as the famous saying from Peter Drucker goes, Bermiss continued. “I think culture needs to be aligned with strategy and align with the context. And when you have that alignment, then you’re really … setting yourself up for success because culture by itself is not better than a strategy. It needs to be aligned right.”

Bermiss suggested that the kind of culture that’s most aligned with success is a learning culture.

“It’s a culture where part of our norm is that we question things,” he explained. “We attempt to bring in new information. We attempt to change. We try new stuff. That’s a part of who we are. And so, in an ideal situation, the norm that you hold close or that that you strongly believe is that we have the capacity to change when necessary.”

Three Key Components of a Learning Culture

Bermiss emphasized that it’s not the board’s role to establish the organization’s culture per se. But the board can support the organization having a learning culture by asking staff leaders key questions about psychological safety, failure and growth.

Psychological safety. Bermiss talked about research that was done into hospital error rates. Based on the error rates alone, some hospitals looked like they were way better. But then researchers looked at the level of psychological safety employees felt. Where the reported error rates were low, it turned out, psychological safety was also very low. In other words, where employees were afraid to report errors, the error rates were low.

“This is something that you can probably assess, whether or not there’s psychological safety within the credit union,” Bermiss said. “For the most part I find credit unions to be very safe places, but you might find there’s certain areas where there is not, and this can be driven by a manager or someone who ... believes in a tight ship and making sure people aren’t screwing up. And those can be good things because you want people to run a tight ship. But psychological safety is really important for the culture.”

Failure. Bermiss described two models for awarding grants to support scientific research. The model of the National Institutes of Health requires applicants to give lots of detail about their plans and make assurances that they can deliver results. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute model, in contrast, urges researchers in its investigator program to take risks and embrace the unknown. “They give money to researchers, not for any project, but they say, ‘Okay, we believe in you,’” he said. Interestingly, the Howard Hughes researchers win more awards and produce more original research and citations. They also have way more failures.

“Obviously I’m not telling you (that) you should fail,” Bermiss said. “But part of being a learning organization is recognizing that sometimes we’re going to invest in people and they’re not going to be successful. And what’s really important is that that’s part of the equation. We know people are going to fail, but we still encourage them to keep trying.”

Growth mindset. Bermiss said that research into the education of young children suggests that emphasizing intelligence as what will carry a student forward can be detrimental. “People with a fixed mindset believe that they inherently have some kind of skill or talent. And so, if you are talented, things should come easy to you. You’ll do well … because you are good.” In contrast, people with a growth mindset espouse the idea that people do well based on the effort they put forth. So, if someone is performing well, it’s because they worked hard, because they tried.

“Mindset is really important,” Bermiss emphasized, “because people will not always hit the ground running and ... do well. Some of them are going to fail.” And a fixed mindset will set them back when they experience failure, whereas a growth mindset will put them in a position to try again, possibly in a new way.

“So how you all interact with one another (on the board), how you all think about ideas … will shape the culture that the organization ends up having,” Bermiss said.

Lisa Hochgraf is CUES’ senior editor.