7 minutes

5 ways to unite staff and volunteers for good governance

We had a colleague once who used to say that trust is “the residue of promises fulfilled.” It’s a pretty good working definition, as definitions go. It’s simple, straightforward, and likely one that most people can identify with. You trust those that you can rely on; those that have come through for you in the past are most likely to come through for you in the future. You’re probably more drawn to the types of people in your life who do what they say they are going to do, and we bet that you avoid the other type—the kind that disappoint and fail to follow through.

For years, we’ve been surveying credit union leaders around the country and, out of the more than 50 questions that we’ve been asking them, there’s one we’ve always identified as among the most important: How effective is your board at building a leadership culture of trust?

Then, after years of surveying individual credit unions, we synthesized the data from multiple credit unions and learned a lot. (You can read the fruits of our labors in the recently published study entitled “The State of Credit Union Governance, 2018: Five Data-Driven Recommendations for Future Success.”)

We found a significant difference in perceptions between credit unions’ senior staff and volunteers (board and supervisory committee members) on matters of trust.

The numbers may surprise you; we know that they surprised us.

If you consider trust to be an essential building block of a cooperative’s leadership culture, as we do, the numbers may also concern you.

While we identify 10 elements of an effective board culture including engagement, inquiry, curiosity, respect, learning, teamwork, accountability, service and diligence, it’s the element of trust that undergirds them all. Without trust, you’re likely in real trouble. Conflict spikes up, relationships fray, efficiency plummets and morale ends up in the basement.

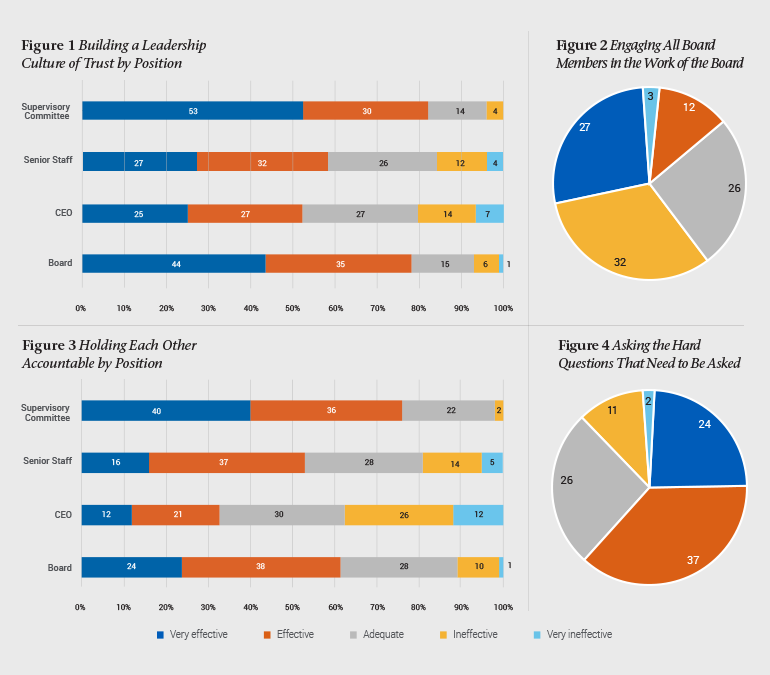

Overall, just 27 percent of senior staff and 25 percent of CEOs that we surveyed reported that their boards were “very effective” at building leadership cultures of trust, and a critical mass of them (42 percent of senior staff and 48 percent of CEOs) thought that their boards were only “adequate,” “ineffective” or “very ineffective” at doing so! See Figure 1: Building a Leadership Culture of Trust by Position.

There’s also a clear gap between what the senior staff and volunteers think. More than 50 percent of supervisory committee members and 40 percent of board members we surveyed reported that the board was very effective at building a leadership culture of trust—indicating a significant perception gap between the two groups.

So, what’s going on here and, more importantly, what should we do about it?

What’s Going on?

What’s Going on?

A credit union board member recently described her board’s culture as “toxic,” and another suggested that there was a “cancer” within. While we certainly recognize that the culture described by these two volunteers is an extreme, we do know that all cultures, including your board’s culture, are living, breathing things that require constant tending and care. And if you’re not paying attention to yours, you’re putting it at risk.

To understand more closely what may be driving these troubling findings on trust, let’s turn back to our recent study and explore three more elements of an effective board culture:

1. Engagement. If trust is the primary element of an effective board culture, engagement runs a close second. You can’t have an effective culture if your board members aren’t engaged. How many times have we heard from our clients (and have you thought to yourself) that there’s a group of board members who just come to board meetings and sit there, never talk, don’t seem prepared and don’t seem to care?

How much trust do you think those board members are engendering? If we go back to our definition of trust—the residue of promises fulfilled—are they keeping the promises they made when they joined the board? Are they serving their CUs to the best of their abilities? Are they engaged, active members of the board? Lending their time, talents and energies? Sadly, the answer is often a resounding, “No.”

Our survey data shows that 41 percent of CU volunteers and staff rate their board members’ engagement as only “adequate” or less than adequate. Board member engagement is—for some CUs—suffering, and such woes are likely having a negative impact on building trust. See Figure 2: Engaging All Board Members in the Work of the Board.

2. Accountability. Merriam-Webster defines accountability as “an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one’s actions.” There’s some good news: Many supervisory committee members believe there is a fair bit of accountability on CU boards.

The not-so-good news is that those actually in the boardroom on a regular basis expressed a much greater degree of concern. Less than 25 percent of board members surveyed think that they’re very effective at holding each other accountable—and the perspective from management is even more critical with only 16 percent of senior staff and 12 percent of CEOs finding boards very effective at holding fellow board members accountable. See Figure 3: Holding Each Other Accountable by Position.

Over time, this lack of accountability is surely having a negative impact on trust. It likely means that some directors are falling short on their promises and their colleagues aren’t respectfully calling them on it.

3. Inquiry. We like to say that one of a board member’s most important jobs is asking good questions. Volunteers will never be a top expert on the CU’s operations, nor should they be. That’s why directors rely on professional CU staff for help. Volunteers must trust but verify; ask questions that staff may not have considered; and provide advice, counsel and oversight that drives success.

Unfortunately, there is some evidence in our report that boards aren’t measuring up in this area. More than a third of our study’s respondents rated their boards as only “adequate” or “less than adequate” at asking the hard questions that need to be asked. See Figure 4: Asking the Hard Questions That Need to Be Asked

The key is to be sure that you’re actively creating a culture of inquiry. Understand your role and speak up. But be careful. Ensure that your culture of inquiry doesn’t become a culture of actual or apparent distrust. That is, trust but verify.

Your questions should be shared for supporting and furthering the CU, not a “got ya” mentality. And don’t jump into the weeds. Keep your questions strategically focused or at the appropriately high end of fiduciary oversight.

What Can Be Done?

If you’ve read carefully, at least some of the answers will have begun to emerge. We’ve listed them here in five suggestions for you to consider:

1. Assess your credit union’s governance effectiveness and culture. If your board hasn’t conducted a governance assessment recently, it’s time to do so. Just like you go to a doctor regularly to evaluate your health, your CU’s governance health and culture should receive its own check-up on a regular basis—usually every two years. This should include a formal assessment process to identify your strengths and challenges and the development of an action plan for improvement.

2. Keep your promises. Say what you are going to do and then do it. Don’t disappoint. Follow through, and if you can’t, be clear why not.

3. Show up. Be prepared. Participate. If you’re not clear about what is needed, ask. Ensure you have job descriptions for directors and officers; make sure you have committee charters, too. These all help to clarify (and quantify) roles and responsibilities.

4. Be accountable and hold others accountable, too. Accountability is a two-way street. Just as we talked about keeping your promises, you need to be sure that your colleagues are keeping their promises, too. Once the roles and responsibilities are clear, and everyone knows them and agrees to them, commit to a culture of accountability. Ensure you have a chair in place who is bold enough and strong enough to lead the charge.

5. Ask the hard questions that need to be asked (and have the hard conversations that need to be had). This last suggestion is perhaps the most challenging of all. It will require you to be open and vulnerable at the same time ... to put your trust in your colleagues and to ask them to put their trust in you. But it’s a must, and as we said, probably your most important role as a board member.

Michael Daigneault, CCD, is CEO of Quantum Governance L3C, Vienna, Va., CUES’ strategic provider for governance services. He has more than 30 years of experience in governance, management, strategy, planning and facilitation, and served as an executive in residence at CUES Governance Leadership Institute.

Jennie Boden serves as the firm’s managing director of strategic relationships and a senior consultant. She has 25 years of experience in the national nonprofit sector and served as the chief staff officer for two nonprofits before coming to Quantum Governance.